My dad died in 1997. As the family gathered, his younger brother told me stories about their days growing up in the boy’s home at Kincumber.

My uncle talked about times that their dad came to visit and how he took them out for fishing or surfing and how much he treasured those days. He described a day that he was in trouble for not recognising his mother in a group of women…

“Um. Sorry, what was that Uncle? Back up a bit. Did you say your dad visited? And your mum was alive too? But you were orphans… in an orphanage. Weren’t you?”

All of my life I had believed my dad was an orphan. I asked my uncle a lot of questions but he had very few answers. The boys were so young when they were put in the home and because they didn’t see her, they didn’t know much of their own history as far as their mother was concerned. My uncle, the youngest of the brothers and having been only 3 at the time, didn’t know why she put them in the home. He didn’t know anything about his life with her before the home. Everything he knew about his mother was everything that I already knew about her. Edna, maiden name Dorney, from Redfern or Waterloo in Sydney.

After that enlightening day, what followed for me was more than 20 years of obsessively searching for the truth about Edna, coupled with an enduring regret that I didn’t ask my dad about his life when I had the chance.

Who was Edna Dorney and what had happened to her that had led her to abandon her three little boys?

My search for Edna Dorney started with trying to find her birth record but the search yielded nothing. She would have been born around 1910 but Edna Dorney was never born, at least not with that name, not in the period of time twenty years before or ten years after 1910, not anywhere in Australia.

The search for Edna Dorney’s birth was frustrating but it wasn’t completely wasted time because it brought me face to face with the Dorneys of Waterloo – more on the Dorneys of Waterloo in a future post.

Next step along the way was to obtain the marriage record of my grandparents.

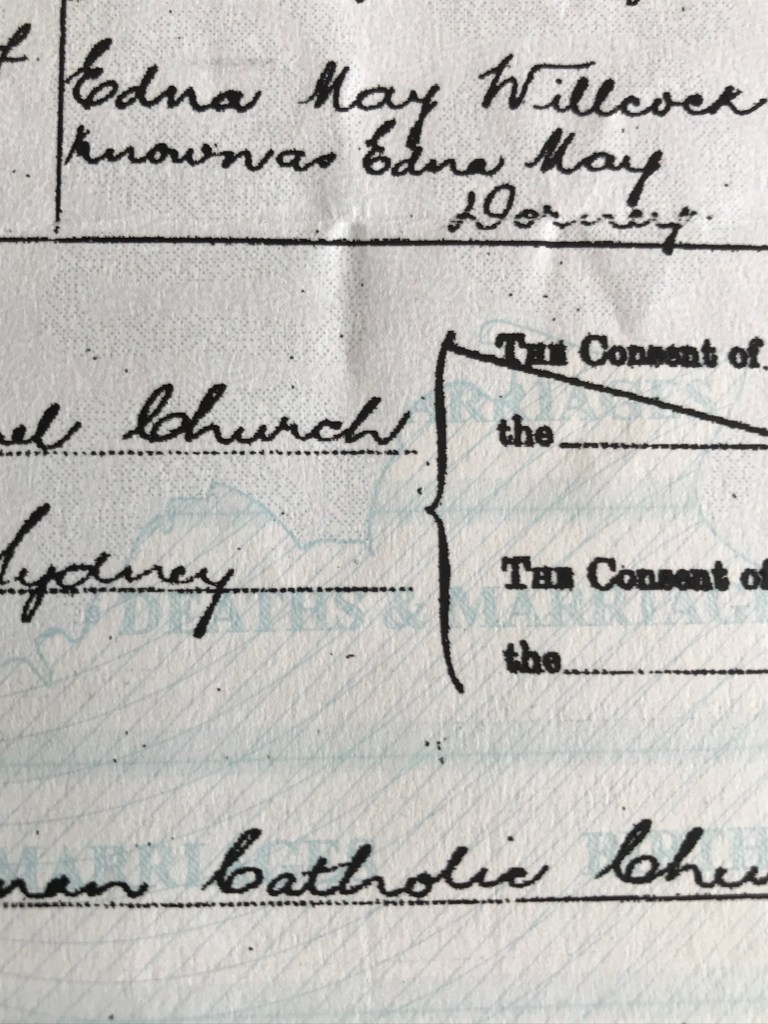

In the marriage record, I found a clue to Edna’s birth. Curiously, her name was recorded as Edna May Willcock, ‘known as’ Edna May Dorney. Edna’s mother was recorded as May Willcock, deceased, and the space where a father’s name should be written, was empty.

I was amazed. Edna now had two surnames and I now had a whole world of questions that I wanted answered.

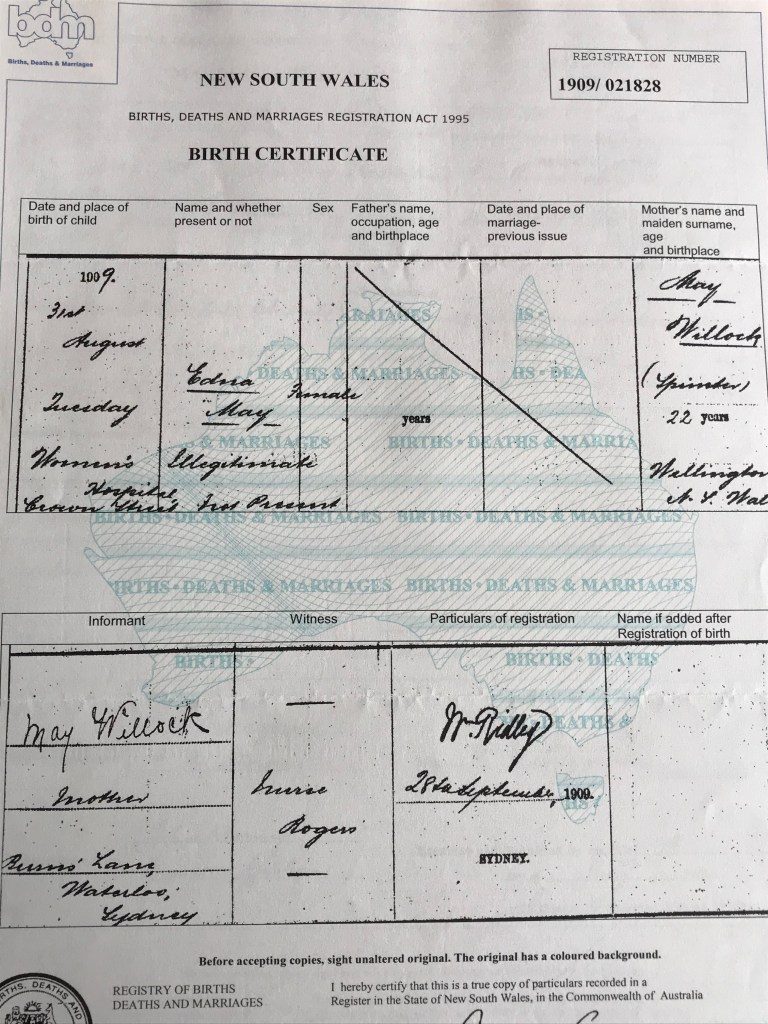

I went back to the birth register and there, waiting patiently to be found, was Edna May Willock, not Willcock, born 1909 at Crown Street hospital in Sydney, mother May Willock, and a big line through the space where the father’s name should be written. The word ‘illegitimate’ leaped off the paper and sliced into my core like a rude profanity.

Illegitimate. Not legitimate.

The pure definition of legitimate means ‘able to be defended with logic or justification; valid.’ The very word ‘illegitimate’ associated with a tiny baby is, in my mind, unthinkable, ludicrous. How can an innocent baby be ‘not valid’? It’s a Christian concept without Christian values. The concept exists because historically, a baby born outside of a marriage was a financial burden on the Church.

But I digress…. let’s get back to the matter at hand. Edna.

Edna’s two surnames opened up a world of curious moments and snippets of people’s lives that bit by bit over the next twenty years would bring me closer to learning the truth about Edna.

Who are you Edna? Who was May Willock? Who was Edna’s father? Will I be able to find you all in the records?