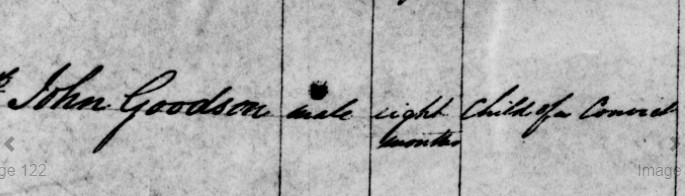

On 24 November 1846, the death of an eight month old baby was recorded in Hobart. His name was John Goodson. His parents were not named, he was simply a ‘child of a convict’. Who was baby John?

From time to time (perhaps too often), female convicts gave birth to babies which were taken from them and housed in nurseries. Don’t let the word ‘nursery’ fool you – convict nurseries were terrible places, notorious for their high infant death rates. The informant at baby John Goodson’s death was Harriett Shaw, the Matroness of the Dynnyrne Nursery – a nursery associated with the Cascades Female Factory in Hobart.

Unless a married convict was already pregnant before she was transported, or she was employed during her period of convict servitude by her husband, a baby born to a female convict during her convict servitude could only be illegitimate and an illegitimate baby usually has the mother’s surname. On that basis, baby John Goodson’s mother was most probably a convict named Goodson.

Pregnant convicts were usually returned to the Government until their baby was born. Then they were able to stay with their babies until they were weaned. At first, weaning occurred at six months, but that was later extended to nine months in an attempt to reduce the death rate of children in the nurseries. After weaning, the mother had to serve six months imprisonment in the Crime Class as punishment for getting pregnant.

The children, if they survived the terrible conditions, remained in the various nurseries until they reached the age of 2 or 3 and then they were moved to the Orphan Schools, unless their mother had gained her freedom in the meantime and could prove she could support the child.

My ancestor Mary Ann Goodson was the only female convict named Goodson in Tasmania in 1846, as far as I can tell. She was 44 and an inmate at Cascades Female Factory so she was in the right place at the right time. But Mary Ann’s record reveals no offences, no punishments. It’s a literal clean sheet.

The only other female convict named Goodson that I have found in Tasmania was Sarah Ann Goodson. Sarah Ann arrived Tasmania in 1840 and in 1843 she married George Alexander in Launceston. If baby John belonged to Sarah Ann, his surname would have been Alexander, he would have been born and died in Launceston and his parents would have been named in the death record. Which all leaves me wondering… who was baby John Goodson? Could he be a member of my family?

I first learned of the existence of baby John when I visited the Cascades site in 2015. At that point I knew I had a female convict ancestor named Mary Ann Goodson. And that was all I knew about her. I was hoping the visit would help me find out more about Mary Ann – instead, my visit turned out to be the catalyst that launched my research rather than providing the ready-made answer on a plate.

I did the public tour and learned about the horrific experiences of the women and children, learned that the women had virtually been loaned out to the local men like library books, returned when they were of no further use. Often they were returned suffering from the effects of various forms of abuse, including being ‘in the family way’.

Perhaps it was a one-eyed exaggerated view – the tour guide was a woman and an actress. Or perhaps it was a very accurate account. At that stage I didn’t know any different so I accepted it as a factual account delivered by a world heritage site.

In the gift shop after the tour I found two A4-sized booklets containing typed lists. One was a list of the names of known inmates and the other was a list of babies and children that were known to have died while they were ‘accommodated’ at Cascades. One book contained Mary Ann’s name, the other book contained baby John’s name. I was already emotionally drained from my tour experience and I have to admit that having zero knowledge of Mary Ann Goodson, at that moment I made a very large assumption – that baby John was the child of Mary Ann and therefore he was mine too. I remember thinking “OMG Mary Ann was a library book!”

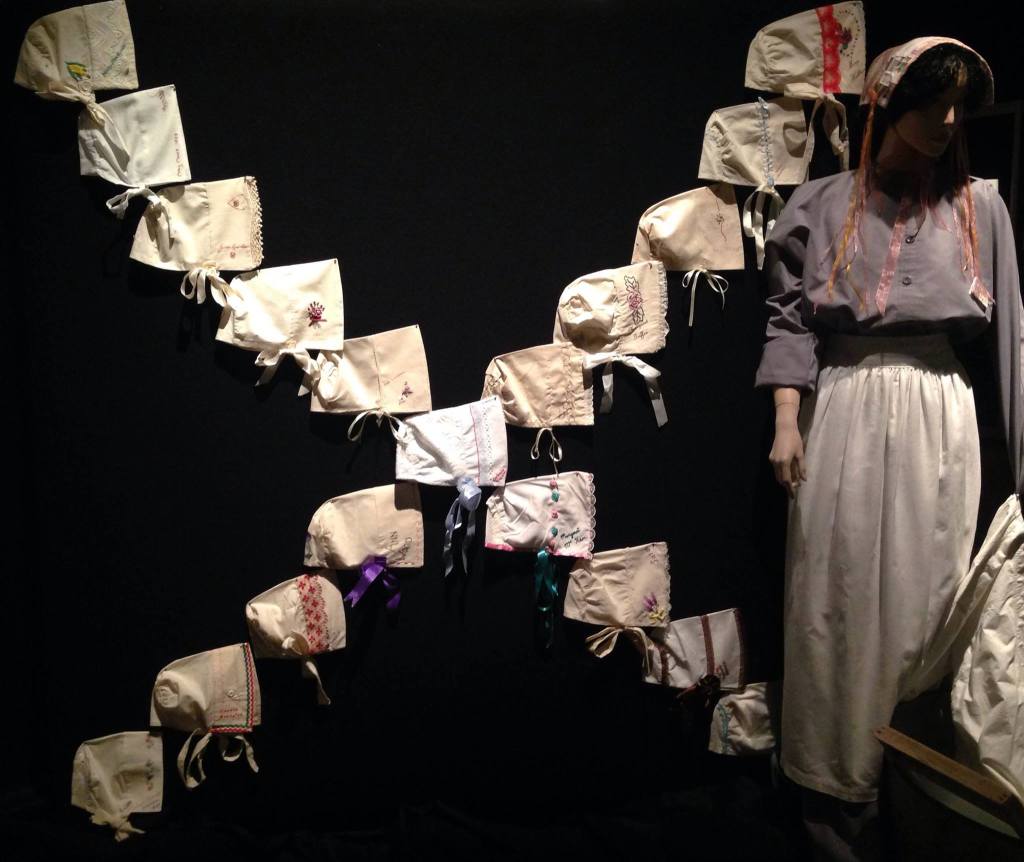

It was in that moment of emotional upheaval that I bumped into Tasmanian artist and Honorary Artist-in-Residence at the Cascades Female Factory Historic Site, Christina Henri. Christina had an art project underway – a bonnet to represent every female convict transported to Australia, decorated by their descendants. That’s tens of thousands of bonnets. For a small fee you could buy a bonnet to decorate and the proceeds went to the historic site. There were smaller ones to represent the babies and children.

Once decorated, the bonnets were added to the artistic display. These displays continue to be erected at prominent and relevant sites across the country. They are beautiful. Each bonnet is exquisite, each one unique and personal. You can find Christina and the project on facebook or the internet – Roses from the Heart is the name of the project.

That day I bought two bonnets – one for Mary Ann and one for baby John. My mother decorated one and my daughter and I decorated the other one. In this way we gals acknowledged our female convict ancestor as a family, and in a very personal way.

After I put the package in the mail to send it to Christina, I realised I hadn’t taken a photograph of our bonnets and now there was no record of things that once existed. It was a modern equivalent of there being no record of an ancestor, ironically akin to our baby John’s records – I can’t find a birth record, there will probably never be proof of baby John’s parentage, and we don’t even know that Goodson is the correct spelling of this baby’s name.

Perhaps he isn’t connected to my family. He was born into an era and environment known for its illiteracy. Perhaps he was a Goodman or a Goodison or a Goodwin. Records are known to be incomplete. If he is a Goodson, perhaps he belongs to an unrelated Goodson convict.

In the end, it doesn’t really matter. He lived, he died, he might be mine and he might not, but he hasn’t and won’t be forgotten.

Welcome to my family baby John.